Dreams: The Face Interview

This interview taken from The Face, February 1989.

The Big Picture by Ian Penman

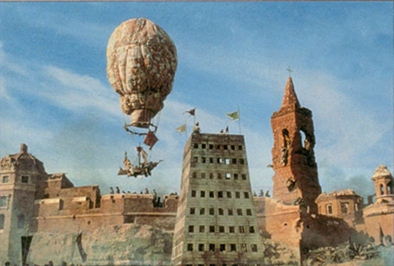

Munchausen, the dictionary warns, is not just a man but a generic, opening onto a realm of exaggeration, towering tales and the people who tell them, who are responsible for them. For director Terry Gilliam, responsibility is an outsize thing, for heís one of cinemaís high rollers; big money goes on big hunches, and the only thing powering the wheel is Gilliamís trust in his own untrammelled eye. Neither visions nor budgets come much bigger than those which combine to produce his latest, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. This Ďprojectí began with Gilliam wrapping up Brazil, having nothing better to do basically, and ending up costing the far side of $43million, having exhausted the filmmaking talent of three continents.

Gilliam has become synonymous with the bigger picture, with some of the big pictures Britain - if we can shoulder this expatriate Yank with our tag - has produced. His irrational viewfinder mind is very un-American - America has never even had a Middle Ages - even if his towering disregard for dollar signs is not. His films fuse the normally separate terrains of adult and child, confounding the distinction that takes the kids to Spielberg and puts us to Streep. If Munchausen is a childís film, itís not the fast-food candy of Back To The Future or Roger Rabbit. Recent American film fantasy of the Lucas school is inherently rational, Manichean, black and white. Gilliam too contrasts cute and cruel, but in a far more extended play on their difference.

Time Bandits was a childís fantasy FX clambering frame which also housed adult British comedy. Thereís a lot of dark urbanity nestling here and his next film, Brazil, took this darker side into a blockbuster fairy tale of flirty paranoia which also doubles as the real film of Orwellís 1984.

Like Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick before him, Gilliam seems less specifically an American filmmaker - not just in the sense of the months, money and murder it takes - than a comfortably global maverick. Gilliam has been based on British soil for a while now (he has a castle that takes up half the hill of Highgate), but his atopical worlds fit into no obvious national fabric - there is nothing characteristic of them save their makerís obvious manic delight at the absurd astronomical universe of cinemaís possibilities.

Gilliamís name burst into life through the interruptive/cohesive animation bites he provided for Monty Python. Python often did its best to turn the company themselves into cartoon, and this persists in Gilliam'í films, where the director routinely regards his actors as objects to be bent out of shape, to be puttied and catapulted, folded and flung at will. But if the Pythons echoed a clear British tradition of logical whimsy, Gilliamís deregulated world is more demonic.

If we have any idea what a trilogy is, the Time Bandits, Brazil and Baron Munchausen might loosely comprise such a thing. Itís one long wonderful life: child (Time Bandits); man (Jonathan Pryce in Brazil); and wise, wizened uber-OAP in Munchausen. Child and the old man have open eyes and minds and their dreams come true. The poor sod at the dystopic centre of Brazil, on the other hand, is flung down a plughole of paranoiac irreality: he dreams of flight, but the dream isnít strong enough to dislodge the mad build-up of the day. The ultimate nightmare image of Brazil consists of apparatus which keeps the eyelids apart; thus is dreamingís digestion and relief done away with.

Itís as if Gilliam were saying you get the world your dreams deserve. One might say the same thing about directors - those creatures of habitual whinge always claim itís the "mediumís fault" that theyíve been disbarred from Art and had to settle instead for the terrifying privation of Beverly Hills luxury, poor lambs. There are directors who expose such hackspeak for the failure of nerve it is; who drag the massive lumber of some dream always just beyond the next budget: Kubrickís unmade Napoleon, Ciminoís unrealisable Heaven, Coppolaís whole careerÖ and Gilliamís Munchausen.

Gilliamís work in Brazil and Munchausen is haunted by a feeling of potential endlessness, the centre always being lost in the frenzy of invention, rippling away into infinitesimal change and addition, their director like some mad burgermeister fashioning spires of dream architecture from 19 different schools of thought. This isnít always necessarily a pleasurable experience to sit through.

Gilliam is a big man: big features, hair the fisticuffs of three different cuts, clothes a palette of colours that look thrown on. When he laughs, the animator is really animated - his sentences modulate into big goofy rising laughs ;like some billowing black cloud taking on an ancient face and about to blow your hat off. Itís an infectious big cave-echo cartoon caveman guffaw - haw haw haw! - which breaks like bottles on some quiet afternoon.

So, to begin the big picture: how pleased is he? How neatly does the end match the original conception?

"Itís quite a bit smaller than the original script. Thatís what I find extraordinary - to find all this shit up there and itís still only about three quarters what we began with. In retrospect, Iím not sure we could ever have gotten the other stuff up on screen. My only fear at the moment is that I may have cut it too tight. Thereís a constant pressure to shorten, the theory being it will reach more people more easily. This is my nightmare - I donít know whether Iíve improved it or hurt it, whether Iíve cut too much, sped it up too much. I just keep thinking of this little bit, these ten minutes I pulled out, an expression or a pauseÖ"

If he has a prime fault itís that he cannot let anything be - but this is also his singularity. Gilliam has got perception like deserts have skies; he plants and scatters tiny details on a Tower of Babel scale - a million chattering images, stitches in a vast fabric. In Gilliamís big picture, every scene is a Christmas stocking, a jack-in-the-box, a potted history. A dwarf flies sideways past the window. Turrets turn into termites. Gilliamís aesthetic is based on ceaselessly adding on, but everything manages to look tightly integral as well.

"I work it out very carefully. I convince myself that itís absolutely logical and makes sense. Then things go wring. Money, time and just sheer mistakes take over, so things are changing all the time. This one was different though - more of a slow build."

You can just picture Gilliam the screenwriter putting in a pencilled insert: falls though into 12th Century. But where do the whirlwinds wing from? These things that end up on screen splitting apart, grasping and falling and reproducing wildly?

"I donít seem to dream as much as I used to. They really take place when Iím awake. I get frightened sometimes because I donít know the difference between dream and awake: it comes and goes, everythingís always shifting. I havenít had any good dreams for a long time; I usually get íem when things are going really bad. Then I dive into the dreams, I escape that wayÖ"

Are entire films just an excuse for the glory of one stubborn image?

"It tends to be like that. The image I wanted most of all for this film was the Baron when his horse is cut in half by a portcullis and heís just riding on the front half of his horse - that was what I wanted to do more than anything. But we lost that before we even started shooting."

Gilliam constantly refers to Munchausen as "this one" like it was something he did every other week, a Sunday afternoon kickaround with jumpers for goalposts. He lulls you into forgetting the budget, the sheer enormity of scale and sweat and organisation. (Maybe this is how he gets the money off people in the first place.)

At some point the idea of making such and such a film - "This film is really for my daughters. We basically invented a narrative to try and hold all these stories together!" - becomes the core of life for a while: stitching a hundred galactic sails together, turning actors into archetypes, spending someone elseís dough. At some point, it becomes an obsession. Gilliam says he can understand how Welles could toil for years on his Quixote and then just leave it to rot in an anonymous bank vault halfway round the globe.

"I actually understand that. When you finally finish it, if it isnít as good as you wanted it to be you just walk away from it as though it had never existed. Itís like too much of your life wasted somehow, you donít want to even acknowledge it."

The previews only remind you how assembly line the whole thing is. Reality - moviehouse darkness, crackle and pop - intrudes. You wish you could keep it at home like a painting and judge it a little longer, forget it for a while, come back to it fresh - maybe turn it to the wall and sulk, or just chuck it away. Instead you go around the world with it.

In Berlin you settle down in a lovely cinema and feel good about it. But then it opens - and that beginning is lit really dark, it took three days to get it all balanced like that, like a late Rembrandt or something, ancient underwater browns of plague and war, but the projection in this goddamn Kraut cinema is like a 30 watt bulb on its last legs, you can barely see the fucking sky up there, and as for the sound - the sound is imply lo-fibre shit sucked through a sieve. The world seems to be full of giant moths nibbling up your perfect vision.

"Itís something thatís made for a huge screen and great sound and I do find it extraordinary, here you spend all this money and you design the thing for something very specific and then youíre shown it in the most awful circumstances."

Cinemaís poetry is, to a great extent, attendant on scale anyway - itís a flickering architecture. Certain films do have to be seen on a big screen or run the risk of being reduced to plot, to Ďissuesí, to purely spoken connotation. (How come our ageís innovations - video, walkman, CD - are uniformly micro?)

"I wanted Munchausen to be big. When I was getting it off the ground it seemed everybody was talking about doing Ďsmall filmsí: Puttnam had gone to LA and everybody was talking Ďsmall filmsí, little filmsÖ and part of the reason to do Munchausen was, ĎLetís do something just the opposite of all that! Letís just do the biggest, most extravagant thing we can think of!í And then you see it being constantly reduced down to something just like mere mortal size.

"I hate all that shit, itís practical for everybody, itís easy to do, everything is reasonableÖ" Gilliam spits out these small words like heís found a centipede in his jumbo burger. "Because nobody wants to go for the big things and the whole point is to do the big thing and be extravagant and lift people out of their normal existence; for better or worse just get them out of that occasionally. Otherwise I think it all just shrivels up and the biggest thing anyone thinks about is their BMW, they aspire to the BMW saloon and thatís it.

"Weíve become too reasonable. When you start dealing with mythic things the English in particular want to reduce everything to the smallest common denominator. I think may be I would have like the Middle Ages. There was a very rich tradition, the Church passed on these great images and great stories. Those things were a much more important part of peopleís lives and now I think people have forgotten all of that stuff."

You can look back on the text of an education and feel angered at all the gaps: the world of the visual, the worlds of mythology. The paradox being that children are especially open to these things - witness their delight in even dodgy movies that exploit these areas.

"You suddenly realise, ĎWait, all this stuff has never been taught me, whatís going on here?í I think thatís why Iíve grabbed onto it. I had a very string religious upbringing which deals with that stuff in a similar way except that it tacks on a lot of other bullshit. But at east youíre used to mythic things. Jesus and his gang, theyíre not a bad crowd of people and theyíre doing Big Things. But the problem with Christianity is that itís got such a limited view, itís such a small view of what really goes on.

" I think people are confused about what they want to make comments about because thereís no Big Picture anymore. They tend to deal with mundane little relationships - does he love her, does she love him? The world is reduced to that now and the Gods have all gone away somewhere.

"The old myths, the Greek myths, are so complicated and wonderful - and incredibly human, thatís whatís nice about them, And nobody deals with them, nobody knows them. A few hundred years ago people understood all the references: you talked about the labours of Hercules and other great stories, and people knew what you were talking about. I donít know what the stories are that people know about nowÖ"

Nightmare on Elm St, probably.

The visual loop, the loop of Time Bandits, is without any obvious precedent. Film, like characters, seemed to have fallen through a hole in the firmament.

"I hear people talking about Munchausen now, saying itís epoch-making or something, and they mean the special effects. I mean, of course people and little cherubs dance in the sky! Those things exist in paintings - theyíve always been there and I donít understand why people are so amazed. Thereís a strange leap happens when something goes up on screen and it seems different than when they see it on a painting or in a book or read about it. I was looking at these Medieval paintings the other day and everybodyís floating in the air and there are those marvellous angels and these strange banners that twirl up and round with the dialogue written on them! If you put anything like that in film itís a very very pale imitation. Iím always disappointed itís not as good as the painting. Yet people seem to be surprised by it!"

Gilliam gathers himself up and flaps some: you half expect helter skelters to pop out of the temples, distorting mirrors to glaze over the eyes.

"What bothers me is that audiences arenít educated any more into seeing these things. They become visually illiterate and when you put things up there they ooh! And aah! Far more that they ought to. Youíre trying to make beautiful images, but theyíre not supposed to dominate the thing, theyíre just supposed to be the vocabulary within which the story is told. It seems to be accepted in animation. I think weíve all gotten caught in this world of naturalism being the truth and naturalism isnít any more truthful that the stuff I do or the stuff Tex Avery does. I mean itís all artifice."

Peter Greenaway said that British cinema carries on as if the entire history of Western art had been forgotten, overlooked. As if no landscape, no light had ever been taken in.

"British cinema used to be visually amazing. Carol Reed, David Lean, Powell and Pressburger - these are really strong visual artists! And then it disappeared, got lost somewhere and we (note the transatlantic "we"!) went theatrical; but the side of theatre that isnít really theatre, itís the Angry Young Man-type of theatre."

Gilliamís visual splendour is halfway between the swooning art of Greenaway/Jarman and the flash of the US Brit pack. Both camps are capable of producing films which are literally stunning: the image overwhelms, has no life of its own.

"But at least itís visual! Ridley (Scott) and that mob are basically commercially oriented. I find the shots so beautiful and yetÖ maybe theyíre just too close to commercials and they have no real substance other than their own beauty. Greenawayís stuff I wish I could sit through because every time I see clips, stills - I love Ďem. Then I watch the film and I lose interest in the thing - because I donít think he likes people, and heís got a real problem there because ultimately theyíre rather important!

"When Iím running short I just run down to the National Gallery and thereís this incredible tradition of painting and ideas. Thereís a whole history out there we should be part of, and I donít know how many people appreciate all that. I think itís a very small number. We actually live in a world of peasants: they just donít know theyíre peasants, they donít till the fields any more. We pretend democracy changed the world and everybodyís more educated and equal - I donít know if they are."

Forgetting: TV is our shrine of forgetfulness. One thing Freud didnít bargain for was a childhood weaned on tiny boxed images. The primal image of love is now found in adverts, which means Love as Money: the family unit has been replaced by the phallic car and coffee jar. TV can reduce not just our images of the world, but our world itself - reduce the world to the square of light right in front of you, which doesnít leave much room for interpretation.

"Television gives you the impression youíre getting information and education and learning something. You look at a commercial and in 30 seconds the number of images that come up is incredible! Except theyíre all the same thing: beautiful girl - car - glassy building. OK, visually theyíre incredible, but theyíre clichťs in the worst possible sense. Thereís just no content in them: cave paintings are more clever than this stuff! Except itís done so beautifully you think youíre seeing something. And pop videos too; itís all flash and filigree.

"Itís one of the reasons I left the States. Iíd reached a point where watching television, seeing those images - the beach at sunset, the gulls, the sea and the beautiful girl walking with me because I use the right deodorant or whatever and weíre in love. And being in California I would find myself on a beautiful beach at sunset with the girl and I couldnít tell whether it was wonderful or whether it was wonderful because it was wonderful and it drove me crazy. The line had become very confused."

We became used to more Ďcomplexí - if compressed - visuals, without knowing how the grammar works, how a particular shot works (on) us.

"I donít know if thatís important or not. Thatís like the magic to me, ultimately weíre still just doing a magic trick, and thereís a lot of ways of doing that trick. In Brazil thereís a pull back at the end and I just know it works - and itís not important whether itís a tracking shot or whatever. Ultimately, thatís what itís got to be about: how it works emotionally.

"I really do want to make the leap away from the world everybody has around them. We start at that premise, we say: all right, this isnít the world you live in; it doesnít look or behave necessarily the same way. I donít like the idea of making naturalistic cinema because television does that very well - people wandering around looking just like everybody else does, having everyday experiences just like everybody elseÖ"

Even TV comedy is very set-oriented, the wide open spaces of Python forgotten.

"Iíd just use a Durer engraving and the next day weíd be thinking about that for a set. Itís only in retrospect you look at it and realise how extraordinary some of the things we were doing were."

Thereís still at times a very explicit Pythonism in his big picture.

" I keep trying to get away from it and in the end always slide back into cheap jokes. Haw haw haw! I think thereís always going to be a battle between the two things. I keep thinking, I just wanted to get rid of it once and for all and finally do a non-funny film, period. But if it isnít funny, itíll be very black, itíll be really dark and that frightens meÖ"